Discovery

In 1963, a team of American and Turkish archeologists surveyed Southeast Turkey, looking for sites of archeological importance. Eight miles from the city of Sanliurfa, they climbed a hill called Göbekli Tepe. They found tools from the Stone Age in the nearby area, and they found carved slabs of stone on the hill itself. Team member Peter Benedict decided it was a long lost Byzantine cemetery and not of great interest. He was very wrong.

It wasn’t until 1994 that the hill was visited again by an archeologist. Prof. Klaus Schmidt looked more carefully than Benedict. He recognized the stone slabs as dating from the Neolithic era, (the Stone Age), about ten to twelve thousand years ago. Schmidt bought a home in Şanlıurfa and began to excavate Göbekli Tepe. It would be his all-consuming project until his death in 2014. He has described the find as a Stone Age sanctuary – a temple. I believe Göbekli Tepe was a major step in the evolution of religion, and the human connection with God. It marks the beginning of civilization, and might be the root of the world’s three great monotheistic religions.

The underground secret

What Schmidt found was a vast collection of stone structures built by Stone Age hunter-gatherers. The construction started about 12,000 years ago and it continued for approximately 2,000 years. There are a total of 20 structures that have been discovered by underground radar. A typical structure consists of a circle of standing pillars built from stones up to 20 feet (6 m) tall and weighing about 20 tons (18,000 kilograms). Each circle is about 30 feet in diameter. One circle has 12 stones spaced around its perimeter and two stones in the middle. Only a few of these circles have been excavated so far, and the site is already massive.

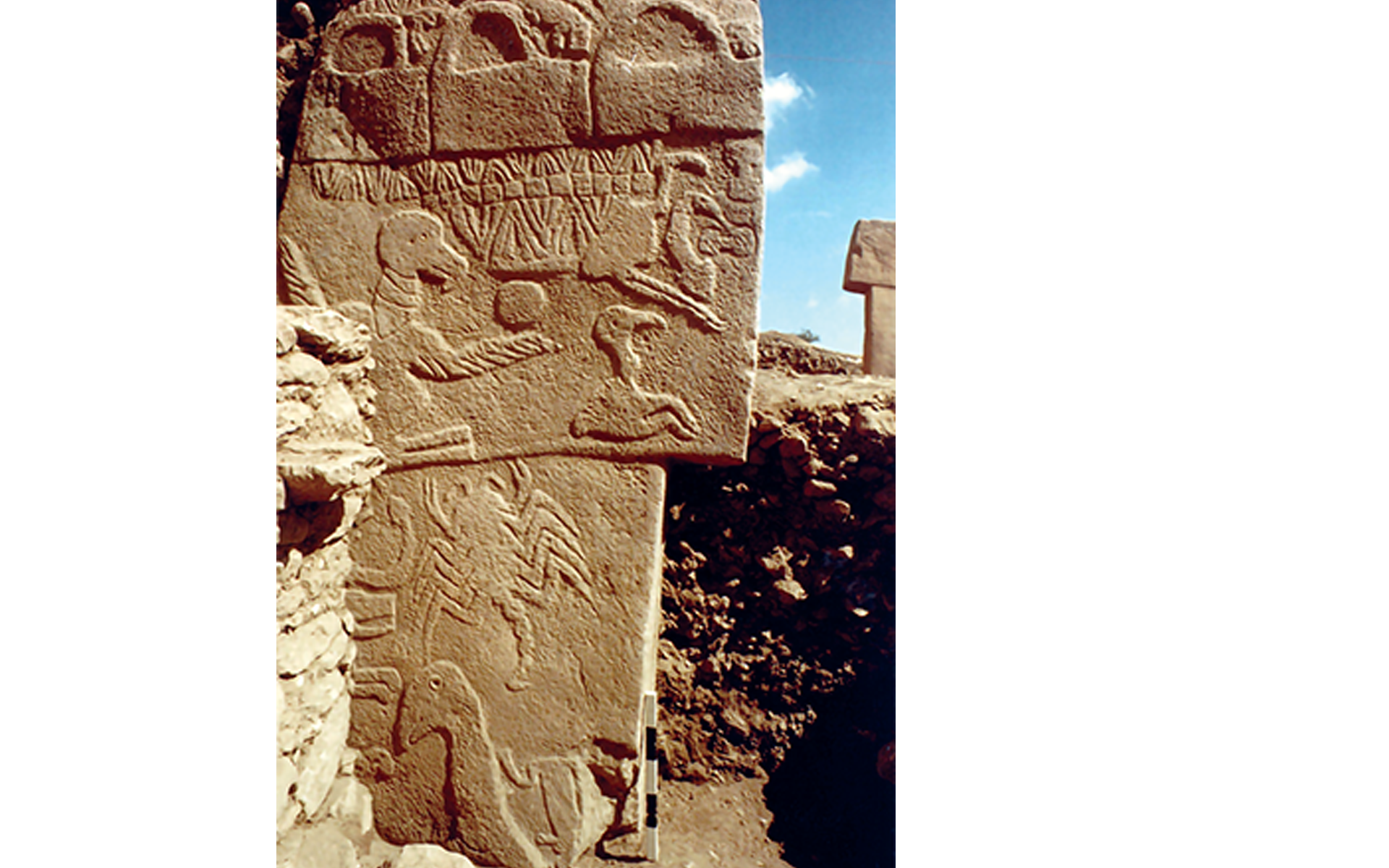

Every circle has two massive T-shaped pillars at the center of the circle. Piled up stones serve as a wall to make this circle an enclosure. Smaller pillars surround the area. Some think these T-shaped pillars once held up a roof of thatching or other material. Others believe they symbolize humans. Most of the pillar carvings are of animals. It is rare to find one which is anthropomorphic, or in the shape of a human. The anthropomorphic pillar in Figure 1 is an exception.

Why was this huge project built? One thing is clear to the excavators—this site was not a place to live. There is no sign of food storage or farming, and it has no material purpose. Its mission was purely a religious one. Schmidt declared it is the oldest known structure built as a temple.

The time line

This amazing complex was built by Stone Age nomads. The oldest portion was finished about 11,000 years ago (9000 BCE).

The Ice Age was just coming to an end. The occupants of what is now Anatolia, Eastern Turkey, were hunter-gatherers. The population was beginning to surge in this area, known today as the Fertile Crescent.

The people may have lived in an encampment for part of the year, but they were fundamentally nomads. They roamed the area gathering fruits, vegetables, and wild grains. They hunted the local animals and knew about their seasonal migrations. It is thought that they did not have pottery, and the wheel was yet to be invented. This era is called Pre Pottery Neolithic Period A (PPNA). Archeologists think these people did not have agriculture. Their unit was a clan or an extended family – a small group of perhaps a dozen or two dozen people – who lived and hunted together.

What did the builders have to work with at that time? Very little. They had tools made of stone, flint, wood, and bone. These people had almost nothing of technology as we think of it today. They did not use metal of any kind. Writing and the wheel were still thousands of years in the future. Yet the people at Göbekli Tepe somehow figured out how to hew a huge rectangular piece of stone out of a solid mountain of rock and shape it into pillars.

These pillars each weighed as much as 20 tons and each was carved out of a solid block of granite. They were pried out and moved a few hundred feet (around 100 meters) using only wooden levers. The pillars were then erected vertically into a base that had been carved into the bedrock. Some researchers estimate this would have required many clans to come together – perhaps 500 people at a time – to both build and feed the builders. It was a project similar to building the pyramids of Egypt.

Why was Göbekli Tepe built?

What caused dozens of independent clans to come together and work as a team to build this elaborate structure, with no apparent material benefit? Where did their ideas of the shape and structure come from? It was not an innovation leading to better food or housing.

Researchers believe the small clans would gather periodically to find mates and to trade objects. Apparently, these groups began to build a sense of higher purpose; an inspiration; a call to do something without materialistic benefits. Researchers surmise they set out to build a beautiful structure for ritual purposes, for spiritual satisfaction. It was a motivation that transcended their everyday life. It was the beginning of a shared religion, a pull that we would later think of as a divine calling – the voice of God! What they heard and what exactly they understood God to be calling them to do, we can only infer from the remains that we see, and how other civilizations developed. The clues we have are in the carvings and decorations that remain on the pillars at Göbekli Tepe.

Historians date the modern idea of a single God without physical body, as known by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, to 3000 BCE. At Göbekli Tepe, most of the adornments are animals, with only a few suggesting the shape of humans. Some of the pillars are deeply carved, with three dimensional versions of animals.

Perhaps the religion of the people at Göbekli Tepe was an animistic one. Maybe they felt that every animal and plant had its own divine spark inside it. Were these carvings aspects of God in their eyes, perhaps some kind of protection from above? Perhaps the force from the other world is represented by a crocodile, a jaguar, or a leopard?

Maybe these animals were totems – symbols representing a clan or some other group of people. Carving these animals, the builders perhaps thought, may have indicated their presence in spirit.

Miracle of the beginning

Writing wasn’t invented until thousands of years after Göbekli Tepe, so we are left to imagine what visions, what religious beliefs, and what concepts of God inspired the people who made the temple; what led them to create this massive series of structures and these carved pillars.

No evidence has been found that anything similar to the massive works that comprise the temple at Göbekli Tepe were built at the same historical moment. The structures here precede the pyramids of Egypt and the stones of Stonehenge by thousands of years. Some unique shared experience or some mystical attraction motivated the clans to come together and to build it. Today, we would call this a religious belief.

Some theorize that there was a class of priests or shamans. This leader, or leadership group, might have had the leadership to convince hundreds of people to assemble every year at Göbekli Tepe and to work on their project. Guiding this construction project was not a small task, nor was it a simple one. It required dozens of clans to work together for centuries. It required more teams of people to supply the necessary food and supplies to equip the workers. It required skilled artists, stone masons, designers, and builders. Clearly, there was a series of people, or leaders, who had the inspiration to know what to build, and the ability to motivate many clans of nomads to work together to build it. The story of Moses and the building of the Tabernacle in the Bible might serve as an example.

The existence of Göbekli Tepe inverts the conventional theory of how all civilizations began. This theory posited that, as time passed, the hunter-gatherers began to domesticate crops and animals. As they did so, they spent more of their time in a fixed location. Clans grew into villages, and villages grew into towns. As populations grew, government emerged, and rituals began. These rituals, the theory holds, became religions, and religious facilities and sacral practices emerged. But Göbekli Tepe suggests that the reverse is true.

Some early religion, some Divine call, led to the early hunter-gatherers’ decision to begin building a ritual center. Lewis Mumford asserted that cities didn’t grow from villages; they grew from “holy sites,” which were visited again and again. It was the shared divine call to Göbekli Tepe, argues Schmidt, that brought the clans and were the “gigantic driving forces” leading to civilization and then to the domestication of animals and the beginnings of agriculture in the Neolithic era.

Figure 1: An anthropomorphic pillar. © DAI Nico Becker. To some, this pillar suggests a human being with his hands folded across his abdomen. Is he wearing a loin cloth or apron, which might represent a priest officiating in a ritual? Perhaps the intent is to remind the viewer of a sacred ritual.

Figure 2: The ancients seem to have used this 10-foot (3-meter) high pillar to tell a different story. The top row seems to be baskets. It includes a vulture and a disk. But the lower portion is often thought to be a scorpion or a spider. Perhaps it is a power symbol or a symbol of danger or death. Schmidt terms these Stone Age mythograms.

Figure 3: A representative deep carving of an other-worldly being. (Photo Dieter Johanes (c) Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. Used with permission.) What is this animal? Why was it significant enough for the Stone Age builders of Göbekli Tepe to carve it into the stone? Schmidt calls it an “otherworldly being.”